The next decades of the seminary's history were shaped above all by Fr. Alexander Schmemann, dean from 1962 until his death in December 1983. Hundreds of St. Vladimir's Seminary alumni were trained under his keen mind, warm humor, and guiding principle: “A seminarian should know only three paths: to the classroom, to the library, and to the chapel”—the liturgical services being the focal point for seminarians’ formation.

David Drillock, Professor of Liturgical Music, Emeritus and St. Vladimir's alumnus, held many different positions at the seminary during Fr. Alexander’s tenure. He fondly remembered his days as a young seminarian:

It was in the summer of 1956, two months before I came to the seminary, that Fr. Georges Florovsky had just left St. Vladimir’s and had begun to teach at Harvard. He was replaced by Fr. Alexander Schmemann, who was appointed as vice-dean of the seminary.

Father Alexander was truly a remarkable man and an exceptional leader. I can still remember the lectures he gave. Nothing was more exciting than going to one of his church history lectures—it was almost like going to the movies! He made ancient church history come alive. All of our professors, Fathers Schmemann and Meyendorff, and Professors Verhovskoy, Kesich, Arseniev, Bogolepov, and so forth, more importantly, were able to convey to us not only their knowledge but also their deep conviction about Orthodoxy: our faith was not a treasure to be merely preserved, but a power, a force, to be taught and preached to the modern world. Because of their commitment and zeal, one couldn’t help but feel that our teachers were in touch with God, and that they were able to convey the wonder and possibility of that sort of holy relationship to us.

—David Drillock, hon. D.D., Professor of Liturgical Music, Emeritus

Father Alexander’s vision for Orthodoxy in America and his energetic leadership brought advances in many areas: increase in support for the seminary on the part of church authorities and Orthodox faithful throughout the country; stabilization of administrative structures; development of the faculty, programs of instruction, and the student body; and acquisition of a permanent campus home.

In 1962, a five-year search for a suitable campus ended with the acquisition of the beautiful property in Westchester County. Saint Vladimir’s sprang up rapidly on the soil that before had belonged to “St. Eleanora’s Convalescent Home for Poor Mothers," a private institution run by the Sisters of Charity of New York City. Saint Eleanora’s had been built by Adrian Iselin as a memorial to his deceased wife, Eleanora, to provide care for mothers unable to afford post-maternity services. (The stately but worn statues of both St. Adrian and St. Eleanora, patrons of Adrian and Eleanora Iselin, still grace the seminary grounds.) Within a few years, after a successful financial drive, new buildings were erected on the property, and housing for faculty and staff was acquired.

In June 1966 the seminary was accepted as an Associate Membership in the American Association of Theological Schools (ATS), becoming fully accredited in 1973. Recognition of the seminary's maturity was given in March 1967, when the Board of Regents of the University of the State of New York granted the seminary the power to award the degree of Bachelor of Divinity (later termed “Master of Divinity”), followed in 1970 by the degree of Master of Theology, in 1985 by the degree of Master of Arts, and in 1988 by the degree of Doctor of Ministry.

In May 1977 a new dormitory and staff residence (aka the “North Dorm”), necessitated by the seminary's continued growth, was dedicated by His Beatitude Elias IV, Patriarch of Antioch; and in 1983, a new chapel, together with a new administrative facility containing the bookstore, classrooms, and office space, was dedicated by His Beatitude Metropolitan Theodosius, then-primate of the Orthodox Church in America (OCA).

Dr. Constance Tarasar, retired Lecturer in Religious Education at St. Vladimir’s, noted this period of burgeoning progress:

Since the late ‘fifties, the seminary had sent several petitions to the Board of Regents of the State of New York for degree-granting status. The acquisition of the Crestwood property, which provided the seminary with “tangible assets,” eliminated one major obstacle; others, namely proof of financial stability, an adequate library to support academic research, additional faculty to lighten teaching loads, and curriculum evaluation, became regular items on the agenda of faculty meetings and committees. One by one, the obstacles were overcome.

A significant factor in the financial support of the seminary was the creation in 1968 of St. Vladimir’s Theological Foundation by a group of concerned laypeople who were committed to the development of a sound program of theological education. The Foundation not only sought to provide fiscal stability for the school but also established a program of retreats held regionally and Orthodox Education Day held annually on the seminary campus.

In less than five years of its move to Crestwood, the student body of the seminary more than doubled. The diversity of programs offered by the school attracted not only candidates for the priesthood, but also young men and women who sought to serve the church in a variety of lay ministries. The growth of the student body also attracted many late vocations and married students, along with abundant numbers of their children.

—A Legacy of Excellence 1938–1988, St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1988

Professor Drillock also offered several vignettes of this mushrooming growth. From his institutional memory, he plucked the “roots,” the beginnings of events and programs that became classically connected with the seminary: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Octet, The Institute of Liturgical Music and Pastoral Practice (commonly referred to as the “Summer Institute”), St. Vladimir’s Theological Foundation, and Orthodox Education Day. He fondly recalled how each endeavor began “organically,” often starting with an informal conversation or an observation, in which, in hindsight, the hand of God could be seen.

The “Octet”

The summer of 1962, the year the seminary moved to Crestwood, marks the origin of “St. Vladimir’s Seminary Octet.” It happened rather incidentally.

In January of 1962, we were still at 537 West 121st Street, in a place called “Reed House,” which was a building of apartments owned by Union Theological Seminary. One of Professor Sergius Verhovskoy’s responsibilities as Dean of Students was to make sure that all of us seminarians were in our rooms by 11 p.m. Many times he would come to the apartment around 10 p.m. and spend the next hour, until 11 o’clock, talking to us in a most informal way. He would speak (in his charming Russian accent) mostly about “feology,” but at times he would also talk about his experiences as a student at St. Sergius Institute in Paris, France.

When he would speak with me, he often spoke about music. He once told me of his experiences as a bass singer in the choir and with real delight told of how one vacation period the student choir at St. Sergius went on tour, singing at the services and presenting concerts in Orthodox churches throughout Western Europe.

Professor Verhovskoy’s story about that vacation tour of the St. Sergius choir came back to me in January of 1962 when I got together eight seminarians to give a short program of music at St. Seraphim’s Church in Manhattan. As it was during the winter break, only a few students were at the seminary, mostly those who were simultaneously enrolled in college. After the program, on our way back to the seminary, we remarked upon how well we had sounded, and the idea of a tour throughout America came to my mind. The next day I spoke with Professor Verhovskoy and Fr. Schmemann about this.

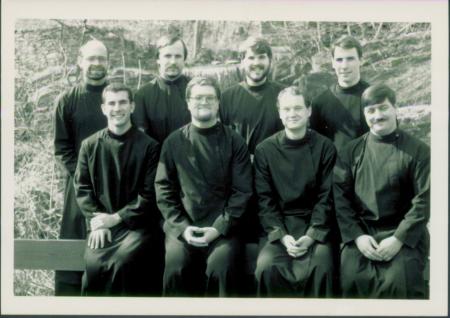

The result was the organization of the first summer “Octet,” with Fr. Schmemann making calls to priests according to an itinerary that my fellow student Alexander Doumouras and I put together. On our tour, each seminarian had his “job”: Alex Doumouras was the economos, Thomas Hopko the preacher, Oleg Olas the driver, and so forth. The first Octet was comprised of the then-young students: Paul Lazor, Paul Kucynda, Thomas Hopko, Alexander Doumouras, Stephen Kopestonsky, Oleg Olas, Peter Tutko, and me, as director and leader; all were eventually ordained to the holy priesthood, except for myself.

That summer of 1962 the Octet visited some 80 parishes throughout the United States, beginning in Philadelphia and going as far west as Cedar Rapids, Iowa. The following summer a second Octet traveled to the west coast, and a third Octet went out the next summer as well. From then on, Octets went on tour through the 20th century every two years.

The Octets were instrumental for several reasons: 1) public relations 2) student recruitment 3) fund raising and 4) promotion of liturgical music—in English, and done well, in a style conducive to worship. Each Octet also transported materials—books, records, icons—that were little known to thousands of Orthodox and non-Orthodox who attended the services and concerts given at local churches in summer by the Octet.

The “Summer Institute”

I held several positions at St. Vladimir’s during my tenure there: Administrative Secretary, Bookstore and SVS Press Manager, Provost, Professor and Director of Music, and, finally, Chief Financial Officer (CF)). But, the titles were insignificant; everyone did whatever it took to keep the vision and the institution afloat.

And that, again, is how what became known as the “Summer Institute” went from a germinating idea to a full-fledged traditional program.

Our alumni used to have a retreat each summer at St. Andrew’s Camp on Lake Oneida, NY. During those retreats, and listening to Fr. Schmemann delivering his awe-inspiring talks, three things kept playing in my mind: 1) How could the seminary help facilitate and actualize the liturgical life on the parish level that Fr. Schmemann taught about in our classrooms? 2) How could a continuing education program be implemented for our clergy and for their choir directors, who needed more training? 3) How could we better use the vacant space on our campus during the summer months?

Thus, it was with the purpose of relating Orthodox liturgical theology with Orthodox liturgical and pastoral practice that the seminary organized the first summer Institute of Liturgical Music and Pastoral Practice in 1978. I remember planning the program together with Fr. Schmemann and our alumnus Fr. Sergei Glagolev, whom we co-opted to organize and direct this first endeavor. A two-track program—one for pastors and one for choir directors and singers—was developed, with a common theme and the same keynote to open each day’s pastoral and music sections.

The Summer Institute was held continuously for 30 years and brought almost two thousand Orthodox pastors, choir directors, singers, and lay persons interested in theology to the seminary campus for one week of intensive study, prayer, and fellowship. On average, the Institute used to attract approximately 80 students, equally divided between clergy and laity. The year that Bishop Kallistos [Ware, now Metropolitan] was the featured speaker, over 200 people attended. However, as the years went on, we watched the demographics of our “summer students” change, to the point that laity outnumbered clergy by almost 80%, and total numbers decreased to approximately 60 students. Perhaps it was time for the development of a new type of program to reach a new generation.

The “Foundation” and “Ed Day”

I firmly believe that St. Vladimir’s Theological Foundation began by God’s inspiration, mysteriously working in rather ordinary circumstances. It happened in the following way.

Much of the seminary’s printing materials for its annual Christmas and Easter appeals, building campaigns, and bookstore catalogues was done by Office Assistance, a company based in Latham, NY. Michael Behuniak was its principal owner and a very close friend of our school, and he was overly generous and kind with his terms for doing business with us. Michael arranged that I, together with Ann Zinzel, the seminary’s faithful secretary, meet with the Director of Development at RPI, who spoke to us about general principles of fundraising used by institutions of higher learning like his. He strongly advised that our seminary, if it were to grow and develop, would need “supporters on a substantial level.” At the time, his words and the level of giving he proposed seemed unattainable for our small seminary. Yet, I knew that we did need a firmer base of support.

As a result of that conversation, in 1968, Fr. Schmemann, Professor Verhovskoy, and I gathered together about twelve friends of the seminary, including Zoran Milkovich, a New York banker and alumnus of St. Vladimir’s. We gave a presentation about the seminary’s programs and its annual operating budget and encouraged the formation of an organization that would promote financial support for theological education in the United States.

This organization soon morphed into “St. Vladimir’s Theological Foundation,” with over 1,600 members giving a minimum of $100 annually; the organization had its own charter, by-laws, and officers, and eventually its own director. Zoran became its first president, and its board met monthly on our campus. We seminary administrators, along with Zoran, would travel the country speaking about the seminary and garnering new members for the Foundation.

Besides giving financial support to St. Vladimir’s, the Foundation organized retreats for its members: an annual retreat held at the seminary during Great Lent and local retreats held in various parishes throughout the country. It organized educational excursions to Russia and Jerusalem, and it sponsored “Orthodox Education Day,” an annual campus event held on the first Saturday in October. Each “Ed Day,” with its varying annual educational theme, has brought together thousands of Orthodox and non-Orthodox visitors to our campus for a day of spiritual, educational, and social fellowship. Crucial to the success of the day are, first of all, our seminarians, who continue to expend tremendous energy each year laboring over set up, tear down, and food service on campus. Additionally, local parishes that supply ethnic foods and extra “hands” on that day are of great support.

Foundation members were a tremendous support for decades, presenting large annual grants for the school’s operating budget and providing a base of loyal friends. Still, as the seminary continued to grow—increasing its enrollment, developing its faculty, and expanding its campus—and demographics changed, it became clear that the seminary would need more supporters on a more “substantial level of giving,” as the Director of Development at RPI had once put it.

Once more, by God’s extraordinary way in perfectly ordinary circumstances, the answer was provided. Just at that time, Lilly Endowment, Inc. gave a grant to the Association of Theological Schools (AtS) to educate theological schools about the “development” and “advancement” of their institutions. I attended their second fully funded seminar, and my eyes were opened; the seminary did indeed need a professional “Office of Development.”

The Board of Trustees, in 1986, officially established an Office of Development, and eventually Fr. Anthony Scott, a dynamic parish priest in the Antiochian Orthdoox Chrsitian Archdiocese and an alumnus of SVS, was hired as our first full-time Director of Development. Fr. Anthony revolutionized fundraising at the seminary, and subsequently, a $20 million Capital Campaign was begun, culminating in the construction of the John G. Rangos Family Building, which houses our library, auditorium, and administrative offices.

Clearly, the seminary was on a new path regarding fundraising. Consequently, the Foundation was dissolved, as the way forward seemed to lie in more modern principles of fundraising and financial support. All of this growth involved change and pain, and certainly missteps occurred during our many steps forward. However, now the seminary, like other theological schools, has a professional “Office of Advancement,” utilizing principles inclusive of diverse bases: from loyal friends with less means, to well-off donors and grant-making foundations that can fund major projects for continued growth and development.

In all of these endeavors, which began in ways that seem so incidental, I now see the hand of God. I was so blessed to be able to be present, to participate, to witness how the Lord opened and closed doors, and to facilitate His will as a worker in His field.

—David Drillock, Professor of Liturgical Music, Emeritus

SVS Press & Bookstore

The extensive publications program begun under Fr. Alexander Schmemann’s deanship has contributed greatly to the seminary’s standing among theological schools. Saint Vladimir's Seminary Press (SVS Press) today is the largest and most active publisher of Orthodox Christian books in the English language, with more than 400 titles in print and a reputation for permitting a free expression of ideas within the breadth of the Orthodox faith, tradition, and history, while insisting on excellence. Saint Vladimir’s faculty continue to be major contributors to this enterprise, acting both as authors and series editors.

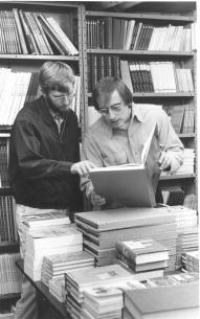

SVS Press traces its beginnings to the urgent need for English-language books about the Orthodox Christian faith, which arose in the mid-1950s. At that time, the multi-ethnic Orthodox student body heard lectures in English, but textbooks were available only in foreign languages, in particular, Russian and Greek. To address this need, lecture notes of the professors were hand-typed or mimeographed for student use. Religious Education Lecturer Sophie Koulomzin gathered her course material for distribution, as well as Alexander Bogolepov, professor of canon law.

Simultaneously, priests in the field were seeking materials to distribute to their parishioners The first attempt by the seminary to respond to this need resulted in the publication of a series of small pamphlets, including “Clergy and Laity” and “Great Lent,” by Fr. Alexander Schmemann. The response by the Church was enthusiastic and encouraging. By 1962, upon relocation to the Crestwood campus, the seminary was ready to begin publication of actual books. Among the first were The Orthodox Pastor by Archbishop John (Shahovskoy) of San Francisco and Revelation of Life Eternal by Nicholas Arseniev. When Fr. Alexander published the full version of his Great Lent in book form in 1969, it sold out within the season of the Great Fast, demonstrating the hunger by clergy and laity for English-language titles about their faith.

During the 25th anniversary year of Fr. Alexander’s repose in 2008–2009, St. Vladimir’s honored his memory in several ways. SVS Press highlighted Fr. Alexander’s major titles in its annual catalog, and the seminary faculty hosted an international symposium in his memory, honoring his work in the field of liturgical theology. Renowned liturgist Archimandrite Robert F. Taft delivered the keynote address for the annual Father Alexander Schmemann Memorial Lecture that year: “The Liturgical Enterprise Twenty-Five Years after Alexander Schmemann (1921-1983): The Man and His Heritage." St. Vladimir’s Seminary Quarterly Vol 53: 2–3, 2009 also was dedicated to his life and work.

Father Alexander’s ever-deepening reflections and writings about the liturgical and sacramental life left an indelible mark not only on the Orthodox Church in America but also on Orthodox churches and believers globally. In his last public sermon, while he battled the cancer that would take his life, he exclaimed: “Everyone capable of thanksgiving is capable of salvation and eternal joy”—a perfect summary of his lifelong work on the centrality of the Eucharist in Orthodox Christian worship.